Foggy Photoshoot

30th June 2020

Why my blog post for Olympus got lost

16th July 2020Do you like wildlife photography? We all have things we do and don’t like in our art. Black and white photographs don’t appeal to a couple of my friends, while I love them. I adore long exposure images, but I know that for others seeing the sea milky smooth isn’t their cup of tea.

Also, I always enjoy abstract photography while some don’t understand it at all. However, I don’t get the same kick from shooting architectural photos. Yet, another friend finds observing the beauty of a building’s design or selecting the way light plays upon its features hugely rewarding.

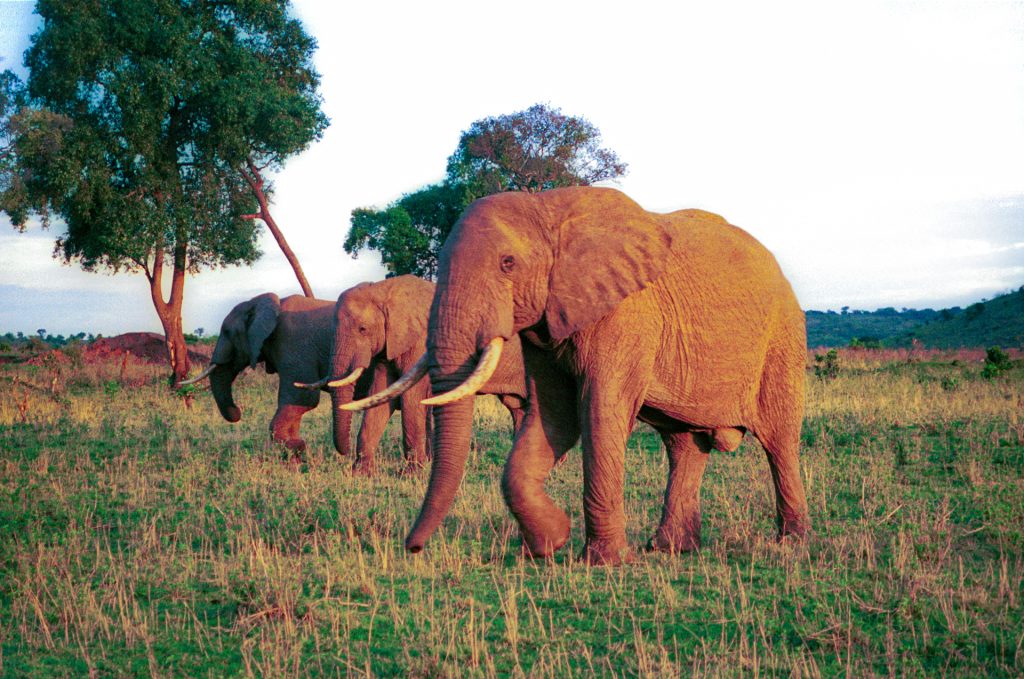

Once considered twee, wildlife photography is for me art at its rawest and best. Our appreciation of shape, colour and form all stem from our appreciation of nature’s aesthetics. Also, wildlife photography is hugely important for conservation.

Zen and the art of wildlife photography

Anyone who enjoys wildlife photography knows the calm feeling of sitting peacefully in stillness and waiting for that perfect moment when capturing an image. Sometimes the animal gets away and you miss the shot. But at other times everything lines up perfectly. Furthermore, you know when you release the shutter you achieved the perfect shot.

Hunting wildlife without killing

I know that some won’t agree with this, but I believe photography fulfils the basic hunting instincts and needs of humans. We use similar vocabulary and shooting techniques. Respecting and studying our subject’s behaviour, we stalk them using stealth and patience. We then aim our camera. Breathing out, we choose the perfect moment to shoot, gently triggering our shutter. We get a good shot if we are skilled enough. Then, we display our photograph upon a wall – we have a trophy showing our image-hunting prowess. Many creative activities bring similar satisfactions.

Photography is what hunting becomes in a civilised culture. It is non-destructive. We leave only our footprints and take solely pictures. Unlike hunting, the subject survives for photographing another day. Furthermore, our shots of the creature are improved upon next time.

A moral conundrum

I am sure that hunting brings a similar feeling of contentment to the hunter. But hunting is destructive not creative. But are there any justifications for it?

When I was a teenager, I camped with the Scouts on a field in Norfolk. Early one morning we heard two shots and shortly afterwards, David, the aged tenant farmer walked past with a brace of rabbits and a 22 rifle tucked under his arm. He had shot each rabbit cleanly between the eyes.

“Rabbit stew for me tonight,” he said as he walked by.

I still have no issue with how the farmer chose to feed himself. The farmer lived off the land and ate meat. Rabbits were abundant and part of his job was to control them. He killed them cleanly. So, it made sense that the meat was eaten.

(The debate of whether we should eat meat or not is a separate one, which I won’t enter into here.)

Organised shoots

I used to think that pheasant shooting could be similarly justified as the birds were eaten. Why? I considered those wild birds having better lives than factory farmed chickens.

But someone I was speaking with recently had found himself unemployed. He had tried to earn money on a pheasant shoot as a beater. Afterwards, dozens of dead birds were left abandoned, unwanted by the hunters. So, the beaters asked the hunt organisers if they could take some for their family to eat. They refused and ordered the carcasses buried by the beaters.

What a waste. That detestable attitude similar to that of those who burned £50 notes in front of homeless people.

Pheasants are not indigenous to the UK, just bred here for hunting. Likewise, farms in France breed red-legged partridges and export them to the UK where they are released for game shooting.

Environmental Damage from Hunting

Then, there’s further harm resulting from or associated with game hunting. For instance, the drainage of moorland for grouse shooting causes ecological damage as well as flooding further downhill. Also, the ongoing illegal persecution of birds of prey by gamekeepers deprives us of our natural heritage. Furthermore, deliberate overpopulation of red deer for shooting leads to massive deforestation and loss of habitat in Scotland.

Trophy Hunting

Trophy hunting is met with universal ire and disgust.

Most of us consider blood sports, and especially trophy hunting, as abhorrent and disgusting. They don’t fit with modern culture or thinking. Shooting an animal just for the joy of its destruction is nothing more than a selfish act of vanity.

Wildlife conservation, photography vs hunting

Opposite to the anger aimed at trophy hunters is a broad respect for wildlife photographers.

Using a camera takes considerably more skill than firing a gun. I speak with the experience of someone who used to regularly shoot with rifles. I am not saying that hunting with a gun requires no knowledge at all to do it well. But shooting with a camera requires greater mastery and skill to achieve a great photo.

Conversely, photography has a positive impact on conservation, raising awareness and respect for our natural world and a desire to save it.

Meanwhile, on balance, hunting destroys nature. Game hunting reserves in Africa claim they help conserve species. But their positive impact is outweighed by the harm done by hunting.

Hunted to near extinction with 98% loss by the 1980s, conservation efforts have doubled its numbers to around 5000 today. This is still tiny compared with the 70,000 in the late 1960s and the hundreds of thousands alive in the 1800s.

According to the Born Free Foundation, over a nine-year period, 290,000 animal trophies from nearly 300 CITES-listed species were exported across the world. Just think what a difference it would make if, instead of guns, hunters carried cameras.

How to start wildlife photography

Where do you start with wildlife photography? Your backyard, garden or the local park are ideal spots.

If you want to photograph wildlife, then give something back in return. Hang a bird feeder to attract birds or put cat food down for hedgehogs in your garden. Place nest boxes on a wall or in a tree, or let a hedge grow tall.

Then learn to sit quietly and wait. Over time birds will get used to you and will come to feed without concern. Robins, blackbirds and starlings particularly can become quite tame.

Wildlife shooting techniques

Looking at the above image of the starling, the convention is that the whole bird should be in focus and so that image is ‘wrong’. To my mind that is poppycock. I wanted to draw attention to the bird’s head feathers and softening the back of the birds tail helped with that.

Get on eye-level with the creature and, just like with portrait photography, focus on the eyes. Because most wildlife moves quickly, select a fast shutter. That, of course, may mean increasing the ISO. Then, a long lens is usual for filling the frame with the subject but getting close is more important.

Next, choosing the correct aperture for getting enough of the creature in focus is essential. Adjust the aperture for sufficient depth of field, but not so much to bring distracting backgrounds into focus.

Birds

Birds must be the most popular wildlife to photograph. Attract them to your garden by feeding them. Place a branch in the ground near the feeder for the birds to perch on. But try to make the images more interesting that just having a bird sitting on a stick. Look for the iridescence in the feathers as the light catches them at just the right angle. Or, study how birds fly up to the feeder and pre-focus on their flight path so you can shoot without the feeder being in the shot.

Wildlife at other locations

Once you have mastered those, try going to the park or local harbour and shoot images of ducks and gulls. If you take food, consider taking something that is nourishing for the birds. Science debunked the myth that bread is bad for ducks. Nevertheless, there is good reason for giving them something healthier. I bake unleavened bread with no salt or sugar, but with seeds, meal worms, sultanas and plenty of fat.

Wildlife Displaying Behaviours Makes Photography More Interesting

To spice up your images, look for classic behaviours. For example, cormorants spreading their wings to dry, or swans putting their heads together forming a heart shape with their necks, or doves puffing themselves up, impressing their mates. Also, see the bigger picture where the subject becomes part of the environment.

You don’t have to shoot classic wildlife portrait images. Instead, try blurring techniques, reflections or extreme close-ups.

On Location Wildlife Photography

There are places in the UK, like the Farne Islands, where you can spend a day near wild birds. At these locations you cannot fail to get good shots. Semi-organised commercial boat trips ferry large groups of people across to the islands. Those trips run in conjunction with the National Trust. I organise a few led photo shoots to the Farnes each year.

Zoos and wildlife parks also offer great opportunities for getting close to animals, especially those you would not usually see. However, fences and windows can get in the way. Shooting close to these barriers can blur them from the picture.

Other nature reserves and sanctuaries have bird hides where you can sit in tranquillity and wait for wildlife to come to you. Sadly, some hides are better positioned than others for photographers. Setting hides far too high above and away from a lake makes good shots of the waterfowl impossible.

Wildlife Photography in the Wilderness

If you get enthusiastic about wildlife photography, then heading out into the wilds and successfully shooting a creature is the pinnacle of achievement. If you get great shots, it means you researched your subject, studied its behaviour, chosen the right equipment, showed patience and had the good luck to capture it.

The art of wildlife photography not only shows the aesthetic beauty of the creature but raises awareness of our natural heritage. Thus, it contributes to conservation. As much as I like street photography and portraiture, to me a well captured image of wildlife carries as much meaning as a picture of a person.

Do you agree or disagree with what I have written? I know the subject of hunting can bring passionate arguments from both sides. If you disagree with me and have constructive arguments that could persuade me away from my point of view, feel free to join in the discussion below, or on social media. Please keep discussions respectful. Abusive comments just mean you are unable to construct a valid argument and lose the debate.

Thank you for reading. As always, I am over the moon if you click the little heart to say you’ve enjoyed the post and shared it for others to read.

I often run wildlife photo shoots. If you want to find out more, please contact me.